The Future of Rights

AI and algorithmically-based applications may help solve humanity’s most pressing problems. But they also come with challenges for civil rights and liberties.

A job screening tool that rejected female applicants.

Software that made real estate ads visible to only certain demographics

License plate readers tracking cars from states that restrict abortion in states that do not.

Facial recognition technology that flagged innocent people as criminal suspects, and prevented migrants with darker complexions from filing claims for asylum.

Artificial Intelligence and algorithmically-based applications are transforming nearly every aspect of society. They can process and analyze massive amounts of data, rapidly identify patterns, and make inferences at a scale, scope, and speed that hold great promise for increasing productivity, reducing costs, improving access to services, and helping solve some of society’s biggest challenges.

But these advances also raise troubling implications for civil rights and liberties. If it fails to comply with existing laws and regulations, the use of AI and algorithms can result in consequences including workplace discrimination, wrongful arrests, and the disclosure of some of the most sensitive information about individuals.

Even more concerning, AI-enabled neurotechnology can now read brain activity and translate a person’s thoughts into text, with vast potential for misuse by corporations and agents of the state. In a new book, The Battle for Your Brain: Defending the Right to Think Freely in the Age of Neurotechnology (St. Martin’s Press), Nita Farahany JD/MA ’04 PhD ’06 proposes a new human right protecting “cognitive liberty” (Read more here).

“[W]e are rapidly heading into a world of brain transparency, in which scientists, doctors, governments, and companies may peer into our brains and minds at will,” writes Farahany, the Robinson O. Everett Distinguished Professor of Law and professor of philosophy. “With our DNA already up for grabs and our smartphones broadcasting our every move, our brains are increasingly the final frontier for privacy.”

The release last fall of ChatGPT, one of several “chatbots” that answer questions, write term papers, even create artwork — and the start of an “AI arms race” among Google, Meta, and other major tech companies — have forced regulators and lawmakers to confront looming concerns over the potential harms of such tools. Their challenge will be to develop guidelines for their lawful and ethical use without squelching U.S. innovation and global competitiveness. At an event in April, U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission Chair Charlotte Burrows described AI as the “new civil rights frontier.”

But many of those threats and risks are already here, especially for vulnerable and marginalized groups whose civil rights may be most imperiled by common applications of these emerging technologies. Those include people of color, who are more likely both to be targeted and to be misidentified by automated cameras and facial recognition technology; people seeking sensitive health services, who may have their movements tracked and shared by their own personal devices as well as public surveillance systems; and people in the criminal legal system, who increasingly have bail, parole, or sentencing decisions determined by algorithms that may be based on biased or inaccurate data.

“As artificial intelligence has become an everyday presence in our daily lives, rather than step in to safeguard our rights, government agencies, including law enforcement, are increasingly trying to deploy these new technologies,” says Brandon Garrett, the L. Neil Williams, Jr. Distinguished Professor of Law and faculty director of the Wilson Center for Science and Justice at Duke Law. “Pressing issues concerning the deployment of AI in criminal cases are not being meaningfully addressed.”

AI and related applications are now so commonly used by employers, lenders, landlords, law enforcement, health systems, government offices, and other businesses and service providers that anyone can experience an intrusion of privacy or be denied a benefit from an automated system using biased or erroneous information. Such ramifications may be difficult, if not impossible, to challenge.

Open for inspection:

Your personal data

Indeed, the ascendance of automated technologies and AI has intensified concerns over the collection and use of data, particularly personal information that individuals consider private.

“In class, I like to talk about privacy as a value separately from privacy as a right,” says Senior Lecturing Fellow Jolynn Dellinger ’93, who teaches classes on privacy law and ethics and technology at the Law School and at Duke Science & Society. “We have to rely on laws to give us the rights we have, in large part. And the United States isn’t the best at providing privacy protections.”

That’s especially true when it comes to data privacy. ChatGPT, a large language model application, answers user prompts by predicting text sequences it has “learned” by analyzing vast quantities of publicly available information on the internet. It and other machine learning models continuously train on text and images, including data about people that is both about them and produced by them. But the use of this data raises fundamental questions on ownership of personal information and the right to keep it private, especially as AI’s ability to draw connections between disparate pieces of data makes it harder to keep information siloed.

“We do not anticipate being watched, followed, and tracked everywhere we go throughout a day. Aggregating data about our public movements permits insight into our lives that is likely not expected by the average person.”

Jolynn Dellinger ’93

“In this age of big data and the digital world we live in, you’re seeing increasing overlaps in the different categorical areas of privacy, and the lack of regulation is becoming more and more significant every day because of all the new things that can be done,” Dellinger says. “Physical, informational, decisional, intellectual privacy can all be at risk when algorithmic decision-making is employed — particularly without a human in the loop.”

Last fall Dellinger began teaching a new seminar, Privacy Law in a Post-Dobbs World: Sex, Contraception, Abortion and Surveillance, that she developed in response to the Supreme Court ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization ending the constitutional right to an abortion. The June 2022 decision has raised fears that people seeking abortions can be surveilled digitally, and that internet search and purchase history, use of mobile apps and devices, communications, and location data could all be used as evidence against individuals accused of violating abortion laws.

“When we go outside, our faces, our conversations, our movements conducted in public are often considered public,” Dellinger says. “But in practice, we rely on practical obscurity. We do not anticipate being watched, followed, and tracked everywhere we go throughout a day. Aggregating data about our public movements permits insight into our lives that is likely not expected by the average person.”

Even before Dobbs, the Veritas Society, a Wisconsin anti-abortion group, was using geolocation data from mobile phones to target digital media ads to “abortion-vulnerable women” as they were visiting abortion clinics.

And the increasing prevalence of automated license plate readers, which feed images of vehicles and license plates from high-speed cameras to algorithms that recognize and translate them into data, means vehicles can be tracked as they travel, and their owners identified. In July, The Sacramento Bee reported that dozens of California law enforcement agencies had shared license plate reader data on out-of-state vehicles with their counterparts in states that ban or limit access to abortion.

Dellinger calls the post-Dobbs landscape “a perfect storm for privacy.”

“Obviously, Dobbs affects your bodily integrity and your physical privacy, and it affects whether you can make decisions for yourself,” she says. “But also, the vast ability of states that are criminalizing abortion to use your information for purposes of surveillance is really scary.”

In August, Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker signed legislation preventing license plate reader data from being shared with out-of-state governments and law enforcement unless they agree not to use it to prosecute people seeking reproductive care. It is the first state to enact such a law.

But the potential illegality of obtaining and using personal data without explicit notice and consent, especially in commercial applications, poses existential questions for companies that build AI-driven systems. ChatGPT was temporarily banned by Italian data regulators this spring over privacy concerns and is facing investigations and lawsuits in other European countries under the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation, which was passed in 2018. Clearview AI, a company that builds and licenses facial recognition technology, has also run afoul of EU regulators and has been fined, sanctioned, and banned in multiple countries.

While there is no comprehensive U.S. federal data privacy law, successful actions have been brought at the state level. Currently, 11 states have comprehensive consumer data privacy laws with varying rights and restrictions; seven have children’s privacy laws; and three — Illinois, Texas, and Washington — have biometric privacy laws, according to Husch Blackwell. In May, Clearview AI settled a class action lawsuit brought by the American Civil Liberties Union in Illinois charging it with violating that state’s 2008 Biometric Information Privacy Act; as part of the settlement Clearview agreed to sell its database only to government agencies and not private companies. The Illinois law was also used to bring a class action lawsuit against Facebook for collecting biometric facial information through a photo tagging tool without consumers’ notice or consent. A $650 million settlement in that case was split among some 1.6 million Illinois Facebook users.

Many states are now considering bills that, like the California Privacy Rights Act that took effect in January, shift the presumption of ownership of personal data to consumers. This summer, Massachusetts state lawmakers introduced a “location shield” bill that would ban tech companies from selling consumers’ cellphone location information.

“People share data selectively. They might share with Facebook, or they might share with an app on their phone, or they might share on a particular site on the internet,” Dellinger explains. “But when all of that data that you have shared in discrete contexts ends up in the same pile, which is what’s happening with data brokers that create dossiers or profiles on people, then that data can be mined for insights about you that certainly you didn’t intend to share and that you may not even know about yourself. It really calls into question your ability to control access to your personal information.”

Risk includes issues of

bias and fairness

In April, the heads of several federal agencies, including the FTC, EEOC, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice, released a joint statement committing to vigorous enforcement of existing civil rights laws and other legal protections, applying them to the use and impact of automated systems, including AI.

Many agencies have had the issue in their sights. The EEOC, for example, has been advising employers on the use of AI for several years. Automated technologies are common in all types of employment settings, and about 80% of employers use some kind of AI powered tool for recruiting and hiring, according to the Society for Human Resource Management. Many large companies now employ HR analytics specialists.

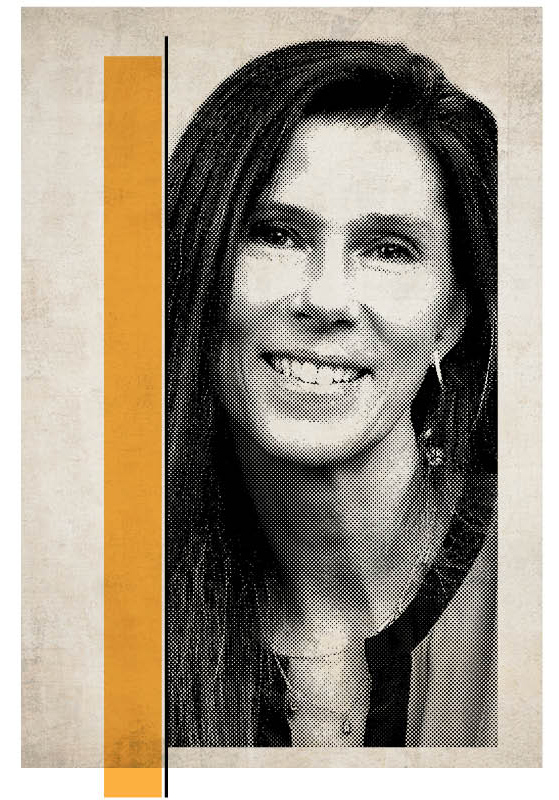

“People are really excited about AI applications and tools,” says Rachel See ’00, who helped shape EEOC policy as an EEOC Commissioner’s senior counsel for AI and algorithmic bias prior to moving to Seyfarth Shaw in June. In the private sector, she now advises clients on AI risk management, governance, and regulatory compliance.

“When used correctly and carefully, AI can help with hiring, create process efficiencies, help identify qualified candidates you might otherwise miss, and meet your DEI goals. If an AI-powered assessment can be more fair and less biased than human processes, there’s a business case for doing it, and doing it right. If you do it wrong, you might violate the law. Whether you use AI or a human process, the law looks at that result.”

See spent more than a dozen years leveraging her background in technology and law while serving in various posts in federal government. Around 2019, she started having conversations with EEOC officials about the impact on the workforce of selection tools that use AI and began to work on the agency’s policy initiatives on how federal anti-discrimination laws apply to employers’ use of such technologies.

AI and algorithmically-based systems are trained on data sets, and when used for a function such as recruiting and hiring, biased data can “teach” them to prefer certain characteristics and exclude otherwise qualified people. For example, when Amazon began developing and testing a proprietary hiring algorithm to recruit for technical careers, the system “learned,” after reviewing past resumes, that successful applicants were typically male, so the algorithm would attempt to predict the gender of the applicant. Amazon says the algorithm was never used to select candidates and ultimately scrapped the project.

Rachel See ’00

“‘The robot made me do it’ is not an effective affirmative defense. You as the employer are owning that decision.”

When machines make biased or discriminatory decisions, just as when humans do, employers are accountable for any violation of laws including Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, the Age Discrimination in Employment Act, the Americans with Disabilities Act, and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act, See says.

“Understanding how our civil rights laws apply to all of these aspects of the employment relationship requires you to delve into not just the law and how the law applies, but how you are using the technology,” she says.

“AI, or machine learning, isn’t present in the statutory text of Title VII or the ADA or any of these other laws, but they apply to a decision that you’re making with the assistance of artificial intelligence, or that you’re letting the bot make on its own. ‘The robot made me do it’ is not an effective affirmative defense. You as the employer are owning that decision.”

Several states are considering legislation on the use of AI and automated systems in the workplace, including a bill in Illinois that would prohibit employers from considering race or zip code as a proxy for race, a Vermont bill that would restrict electronic monitoring of employees, and a Massachusetts bill that would require disclosure of decisions made using algorithms and monitoring. New York City Local Law 144, which took effect in July, requires businesses that use AI in hiring and promotion decisions to disclose their use to job applicants and to subject the tools to a yearly audit for racial and gender bias.

See says employers need to consider their use of such tools in the context of risk management. One resource, AI Risk Management Framework 1.0, released in January by the National Institute of Standards and Technologies (NIST), provides guidance to help organizations assess the trustworthiness of AI-driven systems and utilize them responsibly.

“It provides a way of thinking about risk, and risk includes the risk that the algorithm isn’t doing what you think it does, and that includes bias and fairness,” See says of the NIST document.

The Federal Trade Commission also has taken a lead in enforcing laws within its jurisdiction. Absent a comprehensive federal data privacy law, the FTC’s Bureau of Consumer Protection has resorted to applying sector-specific laws, including the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act, and others that cover financial information and education records.

The agency has ordered WW International (formerly Weight Watchers) to delete data it collected from children and “destroy any algorithms derived from it.” It has also taken action against Amazon for keeping children’s voice recordings captured through its Alexa digital assistant to train its voice recognition algorithms. “Machine learning is no excuse to break the law,” FTC officials wrote in a settlement announcement. “Claims from businesses that data must be indefinitely retained to improve algorithms do not override legal bans on indefinite retention of data.”

Last year the FTC said it would consider broad new rules governing commercial surveillance and use of AI to analyze the data companies collect from consumers’ online activities.

The movement toward added data protections is in step with public sentiment, says Clinical Professor Jeff Ward, director of the Duke Center on Law & Technology, who has taught the law and ethics of AI since 2016. Students today, he says, are especially attuned to privacy considerations.

“It is super apparent to young people what’s going on in a data-driven society,” Ward says. “People see a lot of opportunity in AI, but they are now largely aware of the key biases. It’s worked its way into the culture. People are way more willing to be suspect of technological solutions to technological problems.”

Prying open the “black box”

in criminal justice

The reliance on AI and algorithmically-based systems is especially concerning in matters where human life and liberty are at stake, says Garrett, a leading scholar of criminal justice outcomes, evidence, and constitutional rights. A longtime advocate for more rigorous standards in the forensic sciences — his most recent book, Autopsy of a Crime Lab: Exposing the Flaws in Forensics (University of California Press, 2022), detailed widespread problems in forensic labs and the methods used to analyze evidence — Garrett has in recent scholarship called for transparency and accountability around the use of AI and automated technologies in the criminal legal system, where they are utilized, in varying degrees, at nearly every stage from investigations to judicial decision-making.

“If a forensic tool adds accuracy and value to a criminal investigation, then how it works should be disclosed,” Garrett says.

Used properly, such tools can generate leads in solving crimes and make courts run more efficiently. Predictive algorithms that calculate a defendant’s risk of recidivism based on variables such as age and prior convictions can help divert non-violent defendants from jails and are used to help make decisions in pre-trial detention, sentencing, corrections, and reentry.

But the rapid uptake of technology has also raised issues of bias, discrimination, and privacy, and concern over potential violations of defendants’ constitutional rights, including the right to know and challenge evidence and collection of evidence and the admissibility of evidence from unverifiable sources in a criminal prosecution.

Law enforcement agencies in numerous jurisdictions have adopted automated cameras, license plate readers, and facial recognition systems from companies like Clearview AI, which trained its algorithm on a database of 30 billion images it scraped from the Internet. Clearview AI has also licensed the application to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and the FBI.

“Interpretability should be understood as constitutionally required in most criminal settings.”

Brandon Garrett

Opponents of this type of surveillance say it is disproportionately used in communities of color based on data that reflects decades of over-policing. Similar arguments have been made regarding predictive policing algorithms that determine where to deploy law enforcement resources based on crime and arrest data. Some municipalities, including San Francisco, have banned public surveillance tools, citing those concerns as well as privacy and documented discrepancies in the accuracy of facial identification of people with darker complexions.

While police departments have solved crimes using facial recognition software, they have also made at least six reported wrongful arrests after the technology misidentified innocent people as criminal suspects. All of those wrongfully arrested were Black.

Elana Fogel, assistant clinical professor of law and director of the Criminal Defense Clinic, says the widespread use of public surveillance tools subjects everyone, indiscriminately, to investigation. Prior to joining Duke Law in 2022, Fogel was a federal public defender in San Diego and has long advocated oversight and transparency in the use of emerging science and technologies in law enforcement and combating mass incarceration.

“While we don’t generally have a legal right to privacy while out in public, these surveillance capabilities tend to feel more invasive and hold stronger information-gathering capabilities than another person would be able to capture in passing,” Fogel says. “The presence, or perception, of a police dragnet monitoring us as we all go about our daily lives also runs counter to our ingrained expectation that the Constitution protects us from being followed and searched by law enforcement unless they have a good reason to encroach on our privacy and autonomy.”

What is particularly concerning for individual criminal cases, Fogel says, is that the normalization of constant surveillance can make a person’s experiences of legally improper and invasive policing seem less egregious.

“The practical result is that the strength of those protections erodes, and defense challenges of arrests, evidence, and statements unreasonably obtained are less likely to be granted,” Fogel states.

“The negative impact of these problems is increased by the fact that these technologies replicate racial disparities and discriminatory targeting by being concentrated in so-called “high crime areas.”

The use of non-transparent, or “black box,” AI and algorithmically-based systems — commercially developed products protected by trade secrecy rights that prevent examination and validation of the underlying data and calculation methods — is particularly problematic in criminal legal settings for several reasons, Garrett and Cynthia Rudin write in “The Right to a Glass Box: Rethinking the Use of Artificial Intelligence in Criminal Justice,” forthcoming in Cornell Law Review. The article describes problems with facial recognition technology, predictive policing algorithms, and forensic evidence used to analyze evidence with DNA from multiple parties. Garrett and Rudin, the Earl D. McLean, Jr. Professor of Computer Science, Electrical and Computer Engineering, Statistical Science, Mathematics, and Biostatistics & Bioinformatics at Duke, argue for a strong presumption of transparency and interpretability.

“First, regarding data, criminal justice data is often noisy, highly selected and incomplete, and full of errors,” they write. “Second, using glass box AI, we can validate the system and detect and correct errors. Third, interpretability is particularly important in legal settings, where human users of AI, such as police, lawyers, judges, and jurors, cannot fairly and accurately use what they cannot understand.

“Where independent evaluation is not possible or permitted, there are substantial due process and policy concerns with permitting such black box AI results to be used as evidence.”

Garrett and Rudin cite a federal judge’s 2017 ruling ordering the New York City Office of Chief Medical Examiner to reveal the source code of software it used to analyze complex DNA evidence left at a crime. After calculation flaws were discovered, the use of the software was discontinued. But while some judges have ruled evidence from algorithms inadmissible, far more have allowed it and even denied defense attorneys’ requests to have independent experts examine software on the grounds that intellectual property interests could be compromised if developers were compelled to reveal source code. Rather than proprietary systems that “consistently underperform and disguise errors,” they advocate using open tools.

Garrett proposes that legislation require mandatory transparent and interpretable AI, absent a compelling showing of necessity, for most uses by law enforcement agencies in criminal investigations.

“Interpretability should be understood as constitutionally required in most criminal settings,” he says. “So long as the use of AI could result in generation of evidence used to investigate and potentially convict a person, the system should be validated, based on adequate data, and it should be fully interpretable, so that in a criminal case, lawyers, judges, and jurors can understand how the system reached its conclusions.”

Indeed, system transparency will be critical for judges who must assess and determine the admissibility and authenticity of evidence discovered through algorithms that may be trained on biased data or produced by AI, such as deepfakes, said Paul Grimm MJS ’16, the David F. Levi Professor of the Practice of Law and director of the Bolch Judicial Institute.

Speaking in May on the growing use of AI in both the legal profession and the judicial system, Grimm warned of the risk judges face in allowing jurors to see or hear evidence that later turns out to be false.

“How is this evidence that has to be decided going to influence the fact-finder in this case? Does it have the requisite validity and reliability?

“Even if you tell a jury, ‘This is bogus evidence, this is not authentic,’ they saw it. … And even though they know it’s bogus, it impacts the way in which they’re processing that information.”

In such a rapidly evolving landscape, even judges accustomed to reviewing highly technical evidence may need to appoint an impartial technical advisor to vet and explain evidence involving algorithms and AI, Grimm advised. Judges will also need education, and he said he is encouraged by the response to programs the Bolch Judicial Institute has offered.

“It’s not that the evidence is technical in itself; it’s just that there’s something about AI. The concepts are so hard to explain in some of these software applications, how they got the results they did,” Grimm said. “The good news is that when we have had programs for judges in the past on this, there’s been a lot of interest in it. Judges want to get that kind of assistance.”

Judges may be the ultimate gatekeepers of evidence. But as new uses for AI continue to permeate the culture and make their appearance in every aspect of law and the legal system, it will be incumbent on everyone in the profession to become educated and conversant in at least the basics of the technology. Among younger generations of lawyers and law students coming of age in the age of AI, there’s an eagerness to engage with technology they will almost certainly encounter in their careers, according to Ward.

“Concern about AI has grown, but at the same time, young people are really excited about what the technology could mean and don’t really want to enter into a career where people are turning a cold shoulder to it,” Ward says.

“Things are going to change for our students, our graduates, way faster than people realize. So for that reason, they care a lot about it.”

See also:

Proposing a right to cognitive liberty: Nita Farahany JD/MA ’04 PhD ’06 proposes establishing a human right to mental privacy in her new book “The Battle for Your Brain”

AI and Speech: Stuart Benjamin predicts a continuation of the Supreme Court’s historically broad view of free speech as it considers AI-generated content