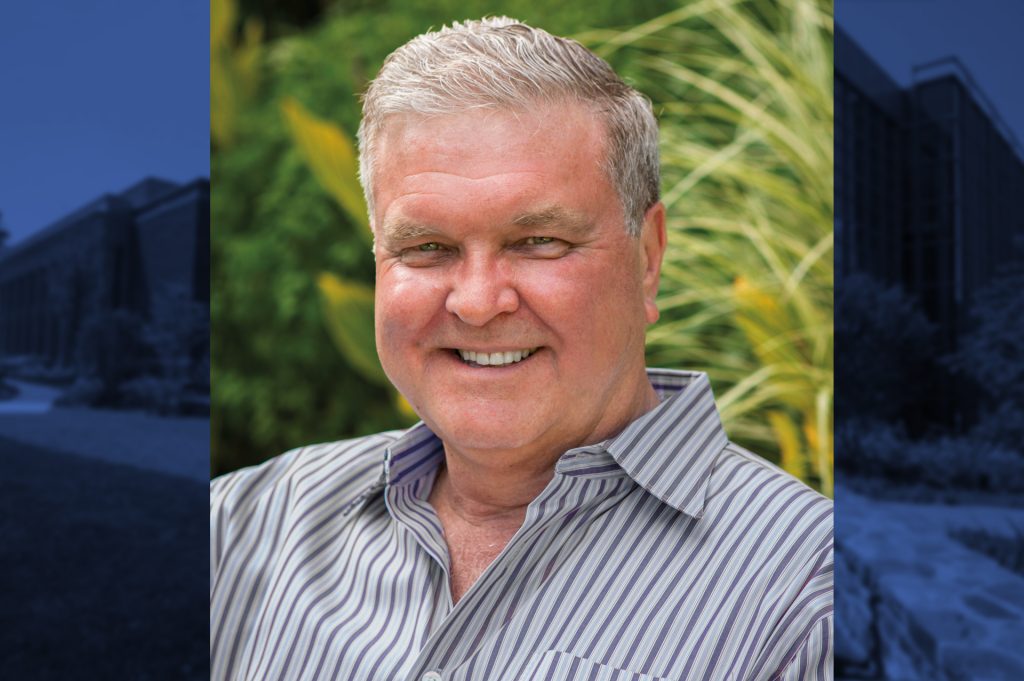

Lawrence G. Baxter retires

An accomplished scholar, teacher, and business executive, Baxter pioneered the study of banking regulation at Duke Law School

Lawrence G. Baxter, an internationally renowned expert in both administrative law and financial regulation whose formidable intellect, global mindset, and bold vision led him to make major contributions in law, business, and society, retired from teaching at Duke Law School in December.

Baxter, the David T. Zhang Professor Emeritus of the Practice of Law, served on the faculty from 1986 to 1995, during which he taught Administrative Law and Criminal Law and created the Law School’s first courses in domestic and international bank regulation. He returned in 2009, when his focus turned to exploring the future of banking regulation after the financial crisis and shaping a new curriculum around the emerging risks to global economies and markets posed by climate change. In between, he spent over a decade as a business executive, steering one of the country’s largest banks to a leading position in online financial services when few others foresaw the transformative potential of the internet.

Before moving to the United States, Baxter was already a rising academic star in South Africa, having written a text that would be used in litigation to fight government apartheid practices. The book is still acclaimed as the seminal interpretation of administrative law in the country.

“Lawrence has an incredibly versatile skill set, having achieved so much success in so many disparate ventures,” says Richard Schmalbeck, the Simpson Thacher & Bartlett Distinguished Professor of Law and Baxter’s colleague during both terms on the faculty.

Sarah Bloom Raskin, the Colin W. Brown Distinguished Professor of the Practice of Law, says Baxter’s name is “synonymous with the appropriate and correct way to understand financial regulation, particularly as it pertains to banks.”

“You let drop in Washington, D.C., … ‘Lawrence Baxter says’ and people automatically assume you know what you are talking about,” Raskin says. “He is infinitely credible as a banker because he is a law professor, and he is infinitely credible as a law professor because he has been a banker.”

“He is infinitely credible as a banker because he is a law professor, and he is infinitely credible as a law professor because he has been a banker.”

— Sarah Bloom Raskin

Baxter maintains that his career has been entirely unplanned. But he acknowledges that his success in multiple realms has also been driven by his “magpie-like” curiosity and a discipline that reflects his father’s frequent admonition, “If you’re going to do it, do it right.”

“Passion has very often been an unacknowledged trigger for me in doing something well,” he says. “And I’m fascinated by the intersection of luck and hard work. Everybody needs a drop of luck, but you don’t get very much of it unless you are positioned right. So my whole career has been the product of lots of luck, but also huge enthusiasm for what I’ve done.”

A “very difficult” decision

Born in Pietermaritzburg, a medium-sized city about an hour inland from South Africa’s eastern coast, Baxter “fell in love with the law” while earning his bachelor’s and law degrees at the University of Natal (now the University of KwaZulu-Natal). After receiving his LLM and Diploma in Legal Studies at the University of Cambridge, he returned to the University of Natal in 1978, joining the law faculty and earning a PhD in administrative law.

After going through compulsory military service — and having been exposed in England to materials about apartheid that were banned in South Africa — Baxter came to realize that he was not being trained to protect the country but rather to maintain a system of oppression against his fellow citizens.

“My eyes were opened, and I saw what was really going on, and I no longer could have the level of patriotism that I’d been told I should have growing up because I didn’t trust the leaders,” he says. “That meant I was opening myself up to instability. I’ve lived my life that way ever since.”

“Everybody needs a drop of luck, but you don’t get very much of it unless you are positioned right.”

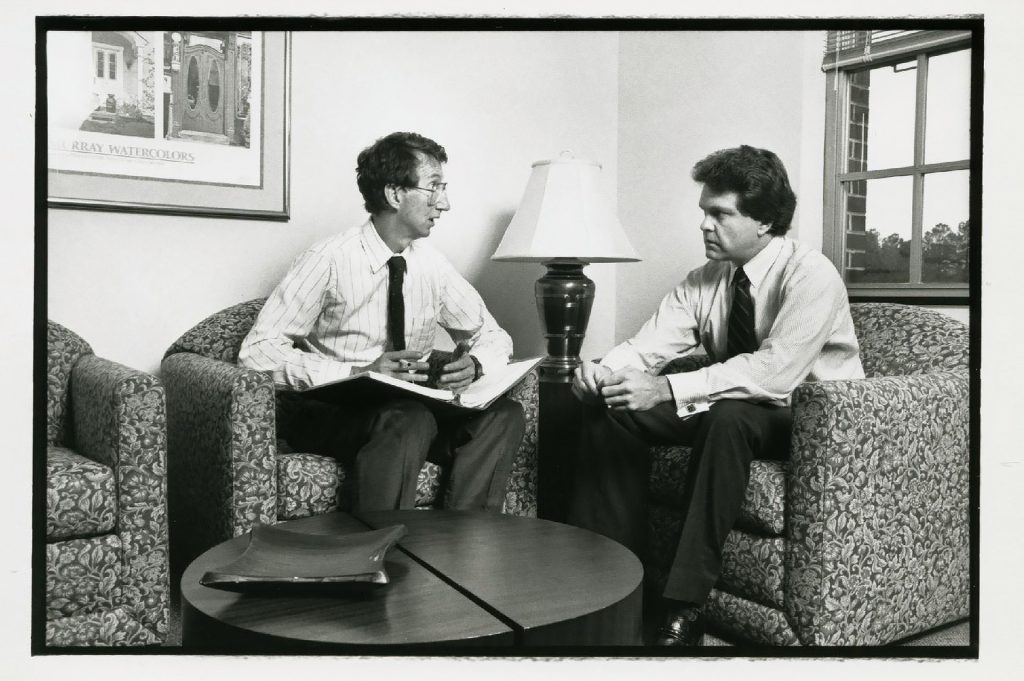

— Lawrence Baxter, pictured here with professor James D. Cox in 1990

By the mid-1980s, Baxter’s Administrative Law (Juta, Cape Town, 1984), regarded as the first comprehensive work on the area and one that reshaped the discipline in South Africa, was emerging as a sort of legal blueprint for challenging government apartheid practices. He credits John Dugard, the eminent South African scholar of international and human rights law who has twice been a visiting professor at Duke Law, with showing him how the law could be leveraged.

“John had learned from the civil rights movement in the U.S.,” Baxter recalls. “He said, ‘You know, the civil rights movement knew how to use the legal process to advance their interests. And we have to do it in South Africa.’

“So that set me off looking at administrative law not just as the narrow technicalities, but what you could do with it. We didn’t have a constitution where you could use challenges to violations of rights, but you could challenge the exercise of ministerial or government discretion under administrative law. And it actually greatly contributed to the eventual collapse of apartheid when it finally happened.”

In 1986 Baxter came to Duke Law for a sabbatical teaching Comparative Administrative Law at the invitation of A. Kenneth Pye, former dean and professor then serving as university chancellor, and then-dean Paul Carrington. Before long, Carrington asked him to join the faculty and he found himself torn by the decision of whether to remain in the U.S. or return home. The political situation was heating up in South Africa, and colleagues and former students litigating against the government were being targeted for bans and worse.

“Those people were in far more danger than I was at that time, though it would probably have evolved if I’d stayed,” Baxter says. “When I accepted the offer from Duke I felt very guilty about not going back.”

Donald L. Horowitz, the James B. Duke Professor Emeritus of Law and Political Science and the author of A Democratic South Africa? Constitutional Engineering in a Divided Society (1991), remembers long conversations with Baxter about the pros and cons of going back versus staying at Duke.

“He was very well established in South Africa. His family was there and he’d been the author of the leading textbook on administrative law in South Africa, so as a young academic he was extremely well-known,” Horowitz says. “Making the decision to stay at Duke was very difficult for him.”

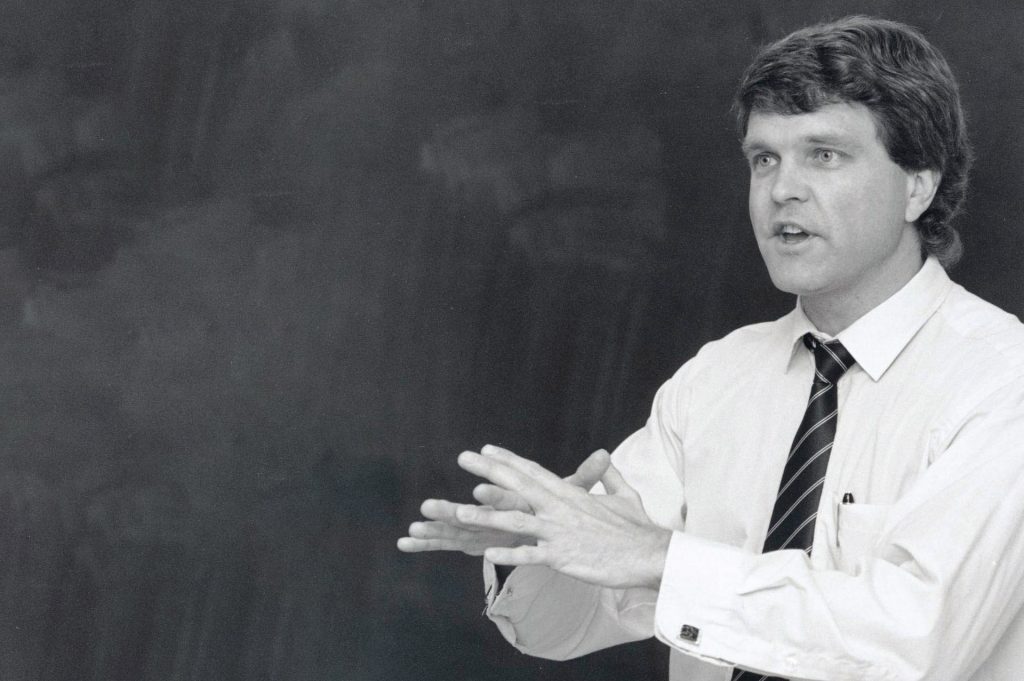

Still in his early 30s, Baxter joined the governing faculty and was “immediately seen as an effective teacher, popular with both students and colleagues, and [he] quickly established himself as an expert in American administrative law,” Schmalbeck says.

But the following year, Baxter received a call that would change his academic path when the Administrative Conference of the United States asked him to research the enforcement powers of federal banking agencies. During interviews with banking officials and regulators, he uncovered the beginnings of the savings and loan crisis that eventually resulted in the failure of over a third of the nation’s S&L institutions at a cost of $160 billion.

“I got to know a lot of regulators at that time quite well and when I would say to them, ‘The numbers don’t add up,’ they would look at me and sort of nod. So they knew I knew,” Baxter recalls.

“I thrive on change. I’m fascinated by the next, the disconnected leap.”

“And as I went around Washington and I was running up the numbers for the amounts that would be needed to bail out what was then hundreds of bankrupt savings and loans around the country, I started to get interested in the business dynamics. I went back to Duke and said, ‘You know, we really need to be teaching bank regulation because nobody teaches it outside of economics departments, and they’re not lawyers.’ And people looked at me sort of funny. I remember [Professor] Walter Dellinger saying, ‘That sounds about as boring as it could possibly get.’ I said, ‘No, it’s very important.’

“All of a sudden, advanced economies realized that their financial regulators needed to coordinate. And I was seen to be ahead of the curve. But I was lucky. I was at the right place at the right time.”

Baxter continued consulting in Washington, working with the Senate Banking Committee to strengthen bank oversight and consumer protection through what became the 1991 Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Improvement Act. He also teamed with faculty colleagues Dellinger and Professor H. Jefferson Powell on a successful Supreme Court appeal for the respondent in Wilder v. Virginia Hospital Association, a case involving hospital Medicaid reimbursement.

But by 1995 Baxter felt he needed concrete business experience to more fully understand the underlying economics and business dynamics driving instability in the U.S. financial industry. He took a sabbatical to work as special counsel for strategic development at Charlotte-based Wachovia, then one of the nation’s largest and strongest banks. After his proposal to cut compliance and regulation costs by consolidating three banks across state lines was adopted, Wachovia asked him to stay on.

“I couldn’t resist it. It was so tempting. There was so much change going on,” he says.

Leading its emerging businesses division, Baxter guided Wachovia’s initial foray into life insurance. Later, as chief e-commerce officer, he pioneered its entry into online banking and built Wachovia’s digital platform into a leading provider of financial services.

“I think there’s a bit of visual and pattern thinking that eclectically assembles things from different parts of my experience,” Baxter says. “I knew the basic shift was going to move from the producers of financial services to the users, because I had just got a computer that had Windows on it, and I realized that changed everything.

“When we were building our online customer base, we had about 50,000 internet users. And we thought, ‘Wow, this is going fast.’ And one of my colleagues said, ‘Let’s go for 100,000.’ And partly out of ignorance, but partly out of enthusiasm and a vision, I said, ‘Why don’t we make it 250,000?’ People were gobsmacked. And we went way past 250,000.

“What started out as something treated with huge skepticism became the busiest channel in the whole company by far. And it shocked the traditional bankers.”

Many who worked with Baxter at Wachovia call him a visionary with talent at both strategy and execution and an ability to lead with integrity and harness the strengths of diverse team members. By 2006 e-commerce was no longer a niche division in the company or in financial services, and he retired from Wachovia and began advising internet startups and consulting for businesses on cybersecurity. But another financial crisis was brewing, caused in part by the collapse of home prices and mortgage-backed securities. Baxter again had a front-row seat as Wachovia lost deposits and funding support and was acquired by Wells Fargo in December 2008 for a fraction of its former value.

“I retired and I thought I was going to go read great books and have great thoughts, and then write a great book,” Baxter says. “None of that happened. Things came up, namely a financial crisis. But apart from that, I also realized retirement was a miserable existence.”

A new chapter and a new focus

At the urging of former Law School colleagues, Baxter returned to Durham in early 2009 to study and teach the causes of the crisis and the evolving post-crash regulatory environment through an interdisciplinary lens of law, public policy, and business. He intended to stay briefly and then return to the technology sector. Instead, he reinvigorated an academic center focused on global financial markets that he would direct for 12 years and taught large classes on banking regulation and derivatives and smaller ones such as Financial Technology and Complex Adaptive Systems and the Law. In July 2018 Baxter was awarded the inaugural Zhang professorship.

“Lo and behold, things developed,” he says. “Duke’s a wonderful place to be.”

He was also becoming increasingly aware of another looming threat. As chair of the Duke University Advisory Committee on Investment Responsibility from 2017 to mid-2022, he was confronted by student demands to divest Duke assets from fossil fuel companies. Impressed, he began to educate himself on climate change.

“Until I became chair of the committee, I knew that it was happening, and I didn’t dispute that global warming was a thing, but I didn’t think it was urgent,” Baxter says. “It’s moving faster and faster now, and I’m sure that a lot of people who never paid attention to climate change will feel like it’s the lightning that we never saw strike. But that urgency has been there for quite a while.”

“I remember one student saying to me, ‘Professor Baxter, could we talk about your carbon footprint?’ My carbon footprint was appalling.”

He became a critic of energy-intensive industries such as cryptocurrency, writing on the environmental impact of digital coin mining and questioning strategies like carbon offsets that don’t cut emissions at their source. In spring 2020 he began teaching a readings class on the impact of climate change on financial markets, which originated when Raskin approached him about the role financial regulation might play in addressing it. With characteristic boldness, he proposed they explore the topic in a semester-long class.

“This course became the foundation by which Lawrence and I started the process of articulating the connections between financial markets and climate change,” Raskin says. “In the early days, it was rudimentary because we were exceedingly careful and disciplined and cautious. In the later days, when we became more confident that we were onto critical connections between climate and markets, the course became a mechanism for students to explore new connections and policy responses, most of which were ahead of the actual work of monetary and financial regulatory policymakers.”

Students were passionate about making an impact on what many call the most pressing issue facing their generation, Baxter says. They also challenged him to rethink his own passion for exotic automobiles, which originated during his youth when his father worked on race cars. A longtime collector whose array of rare, custom, and antique sports cars “classed up the Law School parking lot,” as Schmalbeck jokes, Baxter sold many of his personal vehicles and switched his daily driver to an electric Porsche Taycan.

“I remember one student saying to me, ‘Professor Baxter, could we talk about your carbon footprint?’” he recalls. “My carbon footprint was appalling. Education on this subject has had a big personal impact on me.”

Raskin says Baxter’s bold answer to her question about climate change and financial regulation had a personal impact on her. She has become one of the most prominent voices calling for regulators to get more involved in mitigating climate risks to the stability of the economy and financial system and create more incentives to speed the transition from fossil fuels.

It also, she says, began to shape a new area of study as they convened other top thinkers in law, economics, and public policy, including Professor Gina-Gail Fletcher, in the Regenerative Crisis Response Committee, a group that produced policy papers and recommendations for a more sustainable economy.

At a celebration for Baxter in May, Raskin spoke movingly about their partnership.

“Throughout all of this exploration and collaboration, Lawrence became for me not only the leader in the world of climate-related financial risk, but something even more important than that. He is a friend of the highest caliber — there through thick and thin, through laughter and tears,” she said.

“We all have in our lives those rare people with whom we will try ideas, check how far they go, and decide how we share these ideas, whether our nation can handle them, embrace them, act on them. For me, that is Lawrence.”

Since leaving the Law School, Baxter has been involved in multiple projects, including consulting and serving on boards. He is vice chair of the North Carolina Innovation Council, which facilitates innovation and investment in financial and insurance technology, and a senior advisor on climate financial risk, regulation, and litigation at Kaya Partners, an advisory firm that helps firms address climate change.

“I know I must be immersed in a lot of things,” he says. “I thrive on change. I’m fascinated by the next, the disconnected leap. And I don’t know where that comes from other than it was nurtured by being in a world, from when I was small, of instability.

“For all its challenges, America is still, for me, such an exciting place. And Duke exemplifies the best of it.”