100 Years of Duke Law

As Duke University celebrates its centennial, we’re reflecting on the last 100 years at the law school

Cover illustration by Caitlin Cary

1924

Duke University is established when James B. Duke, through the Indenture of Trust, designates a gift that transformed Trinity College into a comprehensive research university.

1927

The School of Law moves into renovated quarters in the Carr Building on East Campus.

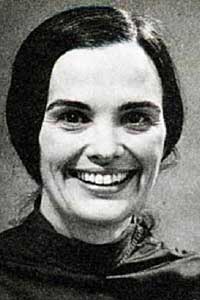

Miriam Cox, a Duke Woman’s College graduate and court reporter, is the first woman student admitted to Duke Law School.

1929

Duke Law adds a third year to the LLB curriculum in 1928-1929.

1930

The School of Law moves into a new building on the Main Quadrangle of the West Campus.

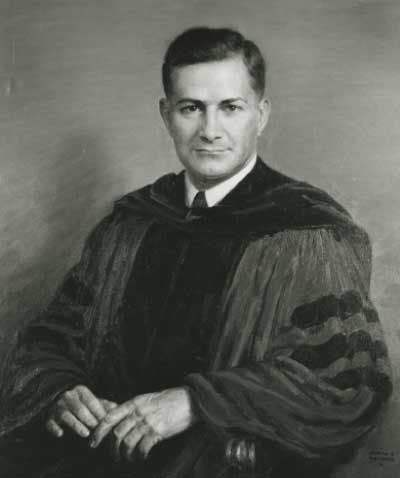

Justin Miller is appointed dean. During Miller’s tenure, the Law School faculty grows substantially.

1931

The Duke Bar Association, modeled on the American Bar Association, is established by the law students.

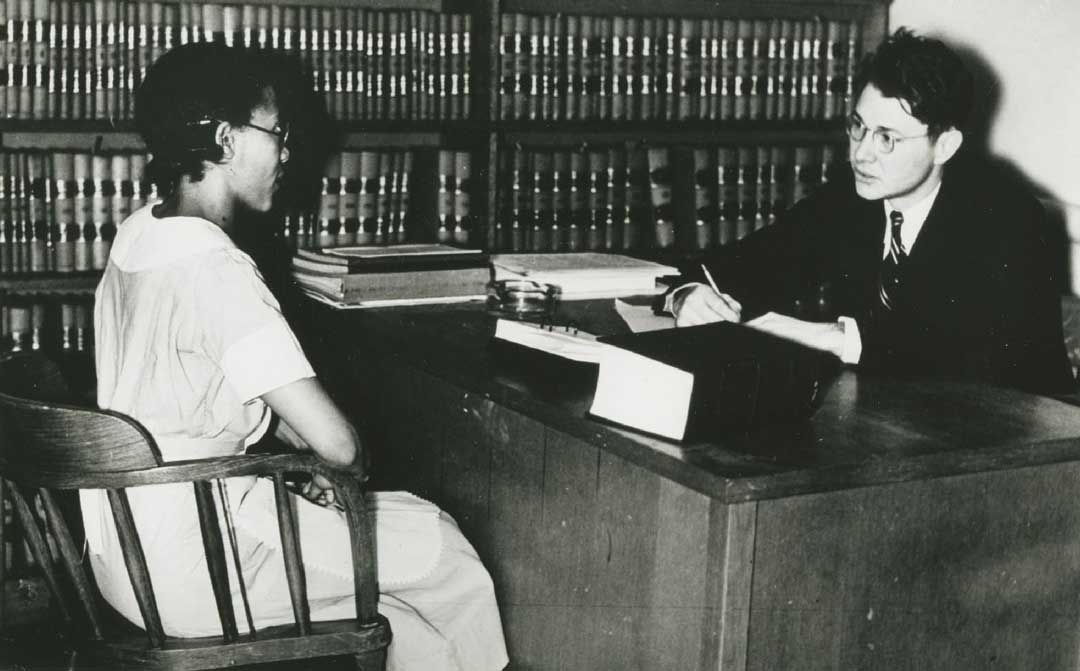

The Duke Legal Aid Clinic, one of the first law school-connected programs of its kind in the country, is established by Professor John S. Bradway.

1938

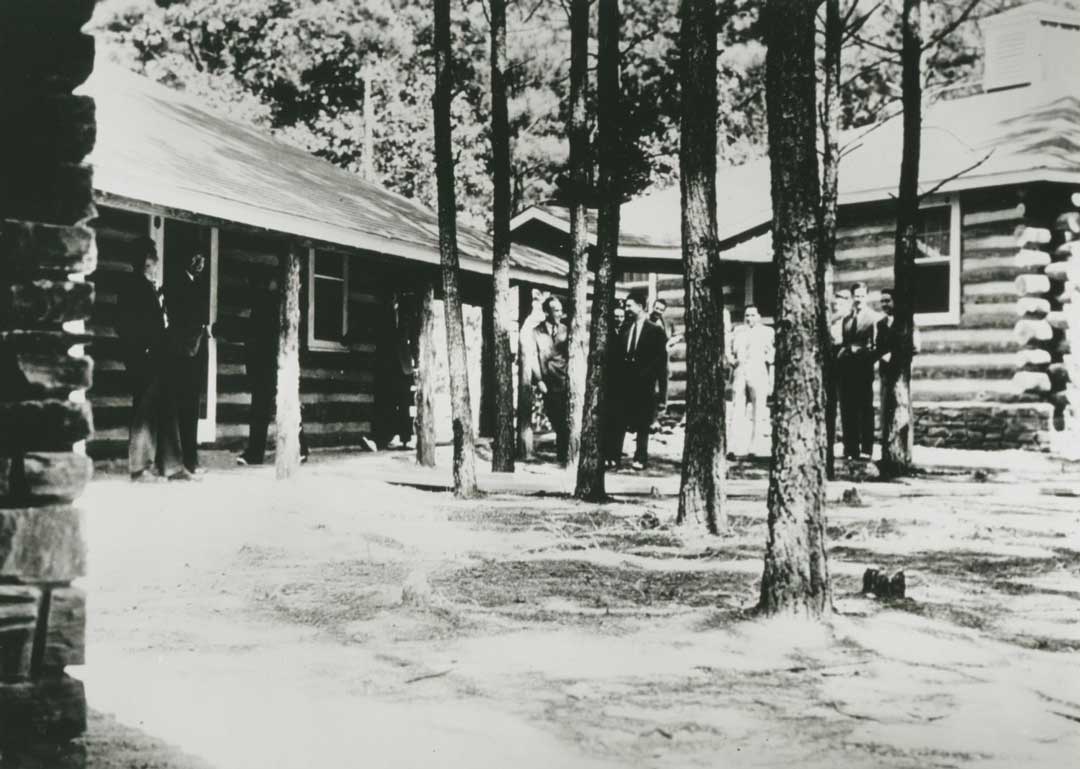

To alleviate a housing shortage for law students, Dean H. Claude Horack oversees the construction of five log cabins on the northern edge of the West Campus.

On Community

Dean Kerry Abrams

Kerry Abrams is James B. Duke and Benjamin N. Duke Dean and Distinguished Professor of Law.

Kerry Abrams is James B. Duke and Benjamin N. Duke Dean and Distinguished Professor of Law.

This essay was originally published in Duke Magazine, Spring 2024. Reprinted with permission.

Community. That’s the word that Duke Law alumni invariably use when I ask them what makes Duke Law special. It doesn’t seem to matter whether they graduated 50 years ago or just received their diplomas. The reason they loved law school, and continue to love Duke, wasn’t the rigorous academic experience or the incredible professional opportunities they were offered — although those aspects of Duke Law are certainly worth celebrating! Instead, it is the friendships forged with classmates, the close relationships with faculty that last well after graduation, and the incredibly supportive alumni — in short, community — that is the most distinctive feature of the Duke Law experience.

Despite enormous change in legal education, the legal profession, and the law, this vibrant and supportive culture has endured for over a century. When James B. Duke signed the Indenture of Trust that created Duke University a century ago, he identified law as one of four professions, along with preaching, teaching, and medicine, that “by precept and example can do most to uplift mankind.” Mr. Duke recognized that being a lawyer is more than just a job. Lawyers are problem solvers. They are trained to see issues from multiple perspectives and help people to resolve seemingly intractable conflicts. They uphold the “rule of law,” which enables individuals to coexist, businesses to flourish, victims to obtain compensation, and government to be held accountable. They protect the institutions that support our democracy — and seek to reform those institutions when they fail to live up to our collective ideals. Our students, faculty, and staff have always understood that the study and practice of law is not about individual achievement. Law is a community enterprise that contributes to the common good.

As we celebrate Duke’s Centennial, it’s worth considering the many ways in which the Law School has grown and changed while maintaining the sense of community that has always been its hallmark. In the 1930s, we established the first law school clinic in the nation to provide free legal services to clients who could not otherwise afford a lawyer and hands-on, experiential education to students. In the 1950s and 1960s, a new dean barnstormed the country recruiting promising students, one of the first steps in transforming us from a regional to a national school. In the 1980s, we went from being a national school to a truly global one, by launching our first international programs and welcoming students from China for the first time. In the 1990s and 2000s, our faculty were pioneers in studying and teaching about the legal and ethical implications of the Internet and we became the national leader in embracing open access to legal scholarship through digitization. In the 2000s and 2010s, we expanded funding, mentorship, and experiential opportunities for students aspiring to careers in public service.

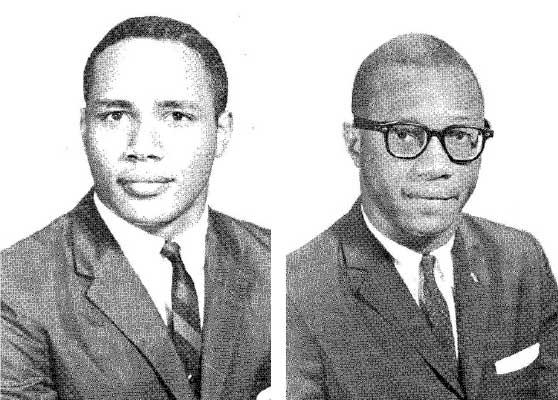

Even as we celebrate the accomplishments of our community, we can also acknowledge that our concept of community has needed to expand — and must continue to do so. In 1927, we admitted our first woman student, Miriam Cox, but it would take nearly a century for women to reach parity in the student body, and they are still fighting for equity in the profession our students join upon graduation. We did not admit a Black student until 1961, when Walter Thaniel Johnson Jr., and David Robinson were two of the first three African Americans to enroll at Duke; the first Black women, Brenda Becton, Karen Bethea-Shields, and Evelyn Cannon, were not admitted for another decade. Over the past decade, we’ve seen a significant increase in students who identify as LGBTQ, multiracial, disabled, or neurodiverse. Our Duke Law community is coming closer to reflecting the diversity of perspectives and experiences of the clients our graduates serve.

Today, Duke Law graduates are leaders in business, government, and public service across the globe. Experiential learning and community service are no longer an innovative experiment but instead an integral part of each student’s education at the Law School. Our faculty are exploring new scholarly terrain, confronting the opportunities and challenges to privacy, liberty, justice, and democracy presented by new technologies such as generative artificial intelligence.

As we move into our next century, Duke Law School is sure to grow and change in ways we cannot begin to imagine. It’s my hope and aspiration that we will meet the challenge of the future with the same sense of common purpose and mutual respect that has served us so well in the past. I like to think that James B. Duke would be amazed and inspired by the Duke Law community we are today, and eager to find out all we will do to “uplift humankind” in the century ahead.

1942-1946

Many faculty members leave for wartime service; student enrollment drops precipitously. The law schools of Duke and Wake Forest combine as a unified operation for the duration of the war.

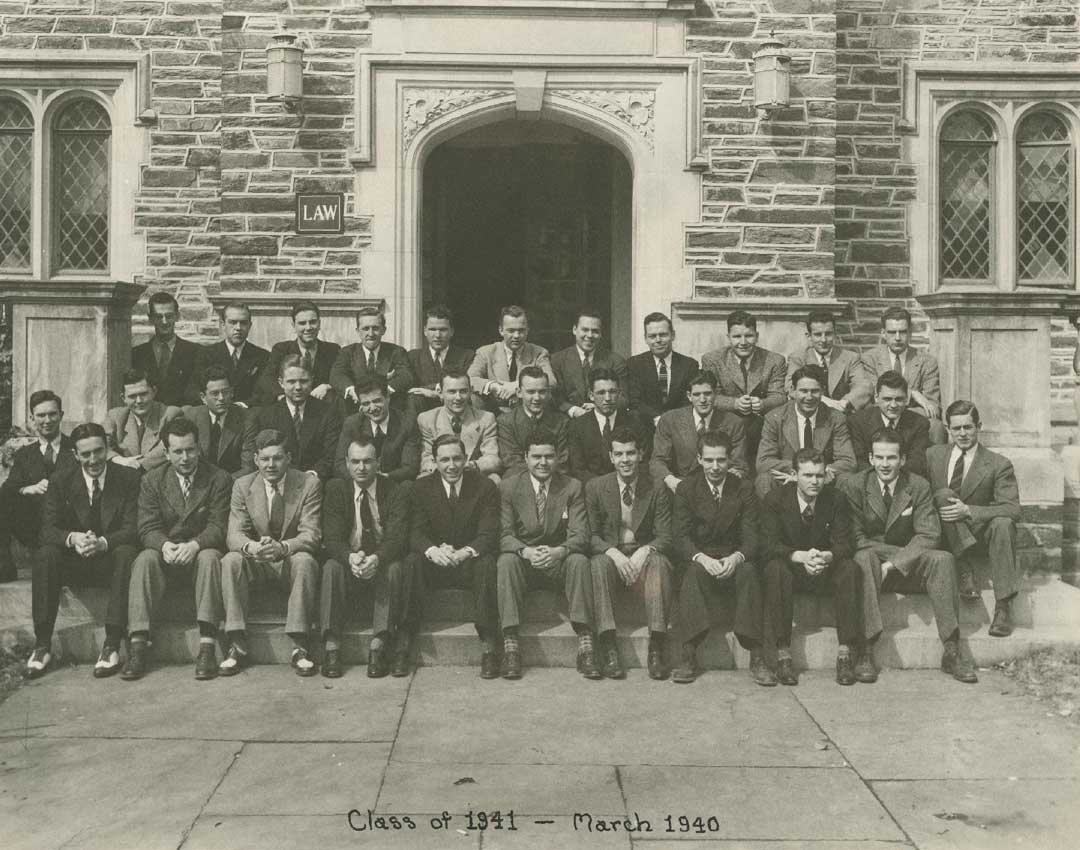

Class of 1941

1947

Returning veterans enroll in numbers that swell the student population for the next five years.

1951

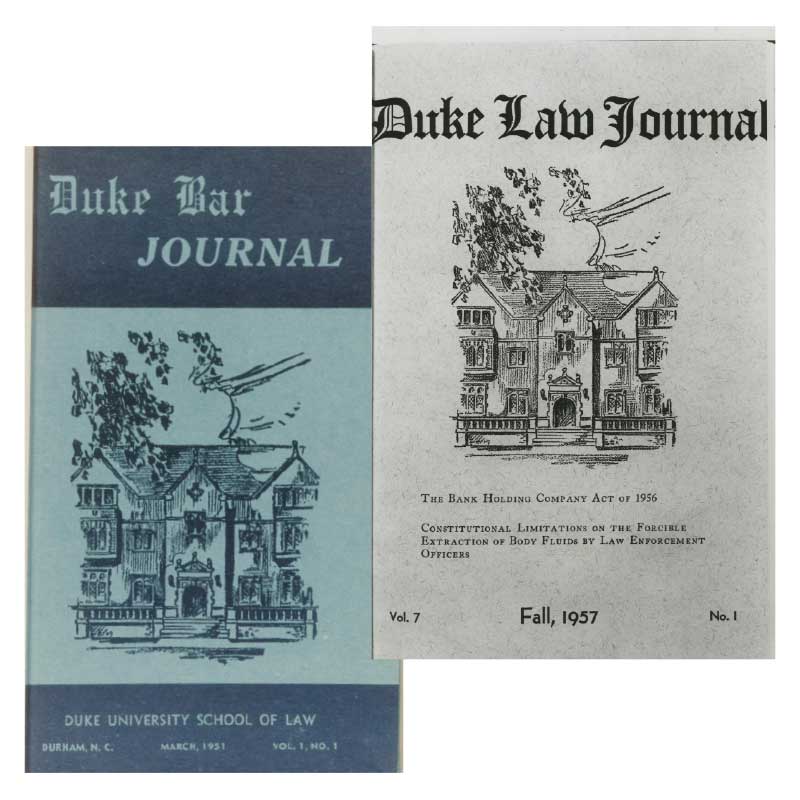

The first issue of the Duke Bar Journal is published. Published twice a year, it is completely student written and edited until 1953 when faculty scholarship is included. In 1957, the Duke Bar Journal is renamed Duke Law Journal.

1957

Professor Elvin R. “Jack” Latty is appointed dean. He was instrumental in Duke Law’s rise to national prominence as a top-tier law school thanks to his ambitious efforts to recruit the strongest students and faculty from across the country.

1961

Walter Thaniel Johnson Jr. and David Robinson II are the first Black students admitted to Duke Law School. Both men graduate in 1964.

1963

The Law School moves into a new building at Towerview Road and Science Drive, built under Dean Latty’s leadership. The Honorable Earl Warren, Chief Justice of the United States, is the principal speaker at the dedication ceremony.

1966

To protest the North Carolina Bar Association’s denial of membership to an African American graduate of the Law School, the faculty approves a resolution to sever ties with the Bar Association until applicants are accepted without discrimination based on race. The Law School re-establishes its connection with the Bar Association in 1969.

1968

The JD replaces the LLB as the most common professional degree in law.

On Globalization

Jennifer D’Arcy Maher ’83

Jennifer D’Arcy Maher ’83 is associate dean emerita for International Studies at Duke Law School, where she was a principal architect and steward of international programs for more than 30 years.

Jennifer D’Arcy Maher ’83 is associate dean emerita for International Studies at Duke Law School, where she was a principal architect and steward of international programs for more than 30 years.

The growth of international and comparative law at Duke Law School can be traced to Paul Carrington, who after arriving as dean in 1978 developed the Master of Laws (LLM) program, a one-year degree for lawyers who had previously studied law outside the United States. While a small number of foreign lawyers had studied informally at Duke, by 1985 the LLM program enrolled ten students from countries including Denmark, Pakistan, and Taiwan.

Dean Carrington established a foundation for international and comparative law teaching and research at Duke Law by hiring international faculty including German-and-U.S.-trained Herbert Bernstein, who along with new faculty member Donald Horowitz supervised the first international graduate of the Doctor of Juridical Science (SJD) in 1985. Carrington brought to Duke noted scholars from across the globe, who helped recruit others and reshaped the SJD program to mirror PhD degrees in other disciplines. Today, Duke SJD graduates serve as law faculty members at institutions far and wide.

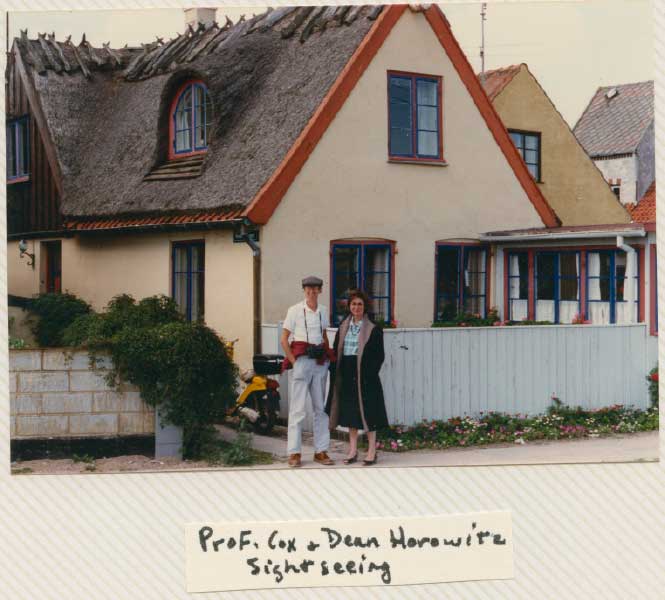

A key figure in the expansion of international programs was Judy Horowitz, Duke Law’s first associate dean for international studies, who recruited, admitted, and advised international LLM students, helped design their academic program, and launched new international and comparative law programs for JD students.

With Dean Carrington and Don Horowitz (her husband), she crafted the innovative JD/LLM degree and launched the Law School’s first overseas summer institute in Copenhagen in 1986. The month-long program moved to Brussels, Geneva, and finally to The Hague, where it has operated since 2018 as the Duke-Leiden Institute in Global and Transnational Law.

International expansion continued with Pamela Gann’s appointment as dean in 1988. Along with Judy Horowitz, Dean Gann made a landmark trip to Asia in 1994 to vet partners for a second summer institute in Hong Kong that operated for 20 years. They visited alumni and law firms, established collaborations with foreign law faculties, and added study abroad exchanges for JD students.

As the LLM program grew, there was a need to give international students a grounding in U.S. law and legal analysis, research, and writing (LARW). I joined the faculty in 1987 to develop that course and taught it for many years. In 1990, Thomas Metzloff began teaching the well-loved class Distinctive Aspects of U.S. Law, which he still teaches today.

International law and programs are now woven into every aspect of Duke Law. This year’s LLM class has 85 students from 35 countries and territories; 13% of students in the JD Class of 2026 are from outside the U.S.; and judges from other countries bring unique perspectives to each new class of the Bolch Judicial Institute’s Master of Laws in Judicial Studies. International and American students exchange cultures and develop their global networks through social events, student groups, and the LLM Ambassadors program that pairs JDs with LLMs.

Mixing talented lawyers from overseas with American JD students brings comparative law discussions into classrooms and broadens Durham’s international population. It also gives LLM students a challenging legal education and a classic American university experience — and they love it. Our international alumni are our best recruiters, helping Duke Law to enroll LLM students from a wide variety of backgrounds through generous donations that include an endowed scholarship in honor of Judy Horowitz and a current-use fund in my name.

It was enormously satisfying, as both teacher and administrator, to contribute to the growth in international studies and programs at Duke Law, and a special privilege to succeed Judy Horowitz for ten years as associate dean.

In May, my successor, Oleg Kobelev, traveled with Dean Kerry Abrams to Hong Kong, Tokyo, and Seoul. They renewed old ties forged on that trip to Asia 30 years ago and established new ones, ensuring Duke Law’s global community will continue to grow for the next 30 years — and beyond.

1972

Patricia H. Marschall becomes Duke Law’s first female faculty member, teaching family law and consumer protection.

Patricia H. Marschall becomes Duke Law’s first female faculty member, teaching family law and consumer protection.

1982

An LLM program for foreign-trained lawyers is established.

Shi Xi-min ’85, the law school’s first Chinese JD student, is admitted and is designated a Nixon Scholar.

International students with Judy Horowitz, Paul Carrington, and James Cox, 1984

1985

The JD/LLM in International and Comparative Law, the first combined degree program of its kind in the country, is inaugurated. The first student graduates from the SJD program, a doctoral degree in law designed for academics from other countries. International programs grow to include the international visiting scholars program, a variety of exchange programs and externship opportunities.

1986

Summer Institute is inaugurated in Copenhagen. It later relocates to Brussels, then Geneva. A second institute is held in Hong Kong from 1995 to 2015. Today, the Duke-Leiden Institute in Global and Transnational Law is held each summer in The Hague, The Netherlands.

1988

Professor Pamela B. Gann ’73 is named dean. She is the first woman, as well as the first Duke Law graduate, to serve as dean.

Law faculty approve the Loan Repayment Assistance Program to assist students who are employed in public interest or government after graduation.

On Leadership

Rob Harrington ’87

Rob Harrington ’87 is a shareholder at Robinson Bradshaw, president elect of the North Carolina Bar Association, and member of the Duke Law Board of Visitors.

Rob Harrington ’87 is a shareholder at Robinson Bradshaw, president elect of the North Carolina Bar Association, and member of the Duke Law Board of Visitors.

Professional and civic leadership is a cornerstone of Duke University and its Duke Law School, but I wasn’t aware of any of this when I entered my freshman year at Duke in 1980 or my first year at the law school in the fall of 1984. I learned of many of the events that reflect the university’s and the Law School’s aspirations of leadership well after graduation. As a law student, I knew only that I had enjoyed my years at Duke and had come to appreciate the university community and its history.

That history includes a revealing example of leadership from the Law School community that I recently learned about while working on a project with the North Carolina Bar Association

The bar association was established in 1899 as an expressly segregated organization, with membership limited to “any white person.” That language survived until 1965, and the association did not admit its first Black members until 1967. Two leaders in the integration of the bar association were Eric Michaux ’66 and Dean Hodge O’Neal.

Michaux came to the law school in 1965 as a transfer from North Carolina Central University’s law school. In 1966, immediately after the bar association revised its constitution to remove the whites-only restriction, Michaux and his brother Henry “Mickey” Michaux sought membership. The association rejected both of their applications in 1966, and multiple subsequent times.

In an interview with the bar association’s board of governors, Eric Michaux told the members, “We [attorneys] have the training, the foresight, the dedicated mind, the sworn and solemn confirmation and conviction to engineer society in a better place in which to live. Therefore, if you are slow to take this step, then society will follow at a snowball pace in either direction.”

In December 1966, in response to Eric Michaux’s rejection, the law school, under Dean O’Neal’s leadership, withdrew its affiliation with the bar association, “until such time as all applicants are accepted for membership … without discrimination based upon race.” In June 1969, Eric Michaux was admitted to membership in the bar association (Mickey Michaux having been admitted in 1968). Two days after Eric Michaux’s admission, the bar association announced that the law school had restored its relationship with the association. Eric Michaux went on to serve as a JAG lawyer in Vietnam and later as a respected North Carolina lawyer and longtime member of the North Carolina Board of Law Examiners.

The Law School’s history is replete with leaders, many of whom I’ve had the good fortune to interact with. Eric Michaux’s leadership in the fight for membership in the North Carolina Bar Association and Duke’s support of his effort mark a little known, but inspiring chapter in the story of Duke Law School.

1995

The Law School website is launched at law.duke.edu.

2000

Professor Katharine T. (Kate) Bartlett is appointed dean. During her tenure, she recruits 17 scholars, establishes new research centers, expands the clinical program, and presides over significant facilities upgrades.

2004

Phase I of an ambitious building construction and renovation project, the reconstruction of two large classrooms and the replacement of the building’s brick façade to match the campus color palette, is completed.

2007

David F. Levi, a former U.S. attorney and federal judge, is appointed dean. During his tenure, Levi presides over major expansions of faculty, research, academic programs, and fundraising, including a threefold increase in student aid.

2008

Two centerpieces of the Law School — Star Commons, a soaring, glass-enclosed gathering space funded by a gift from Stanley and Elizabeth Star, and the J. Michael Goodson Law Library — are dedicated in November.

On Innovation

Jennifer L. Behrens

Jennifer L. Behrens is associate director for administration and scholarship and a senior lecturing fellow at Duke Law, where she has worked since 2006.

Jennifer L. Behrens is associate director for administration and scholarship and a senior lecturing fellow at Duke Law, where she has worked since 2006.

Innovation at Duke Law has taken many forms over the last century. As a result, not everyone may immediately associate the Goodson Law Library with “innovation,” despite a longstanding recognition of libraries’ importance in legal education: Christopher Columbus Langdell, the first dean of Harvard Law, famously (at least to law librarians) observed in 1874 that “[t]he Library is to us what a laboratory is to the chemist.”

Our own “laboratory” began modestly, with 1920s Law School administrators lamenting the library’s inadequate collection and funding. Thanks to the efforts of its first full-time director, William Roalfe, Duke’s Law Library became known as the largest in the South by 1932. Over the decades, the library adapted to changes in legal publishing and technology, moving beyond long shelves of books and journals to today’s combination of e-books, databases, and physical materials, in a space now designed to meet 21st-century scholarly and instructional needs.

This intersection of information and technology positioned Duke on the vanguard of the open access movement for legal scholarship, with many of its successes due at least in part to the late Senior Associate Dean for Information Services Richard A. (“Dick”) Danner (1947–2018). During his 36 years as the director of the Law Library, Danner oversaw a number of initiatives to make legal information more freely accessible online, many of which continue to be managed by the Law Library and Academic Technologies staff today.

In 1998, Duke Law made the full text of its student-edited journals freely accessible online, building upon recommendations by a faculty-student committee. It may be difficult for today’s reader to envision just how forward-thinking this change was in the early years of the World Wide Web, when paid print subscriptions formed the bulk of law journal readership and sites like the Social Sciences Research Network were still new and growing.

Less than a decade later in 2005, Duke Law launched the Faculty Scholarship Repository, another first for American law schools. Providing broader full-text access to the research of our faculty and affiliates through a permanent online archive, the Repository includes final versions of record when permitted by copyright, in addition to the complete archive of student journal publications and their latest issues. Today, the Repository reaches readers around the globe and has surpassed 23 million downloads.

During the Law School’s dedication week in November 2008, Danner organized a meeting of prominent law library directors to discuss open access and other priorities for the future of legal education. The group released the Durham Statement on Open Access to Legal Scholarship in February 2009. The Statement aimed to improve the dissemination of legal scholarly information through formal commitments to open access and free, permanent, electronic publication and archiving. Its impact continues to be relevant today, as noted by the work of a recent Durham Statement Review Task Force, whose Final Report on the status of the Statement’s adoption was released in August 2021 and can be found in (where else?) the Repository.

The Law Library continues its open access efforts today, maintaining the Repository and regularly expanding its collections to include other Duke Law content. Library services and instruction similarly adapt to changing times: early efforts to support the growth of faculty empirical research have evolved into today’s sophisticated Data Lab, while first-year and specialized legal research courses now incorporate generative artificial intelligence and other emerging technologies. Although the Goodson Law Library of today may not bear much physical resemblance to its 1920s version, our innovative “laboratory” spirit endures into the next one hundred years.

2011

Duke LLM in Law and Entrepreneurship is launched in 2011. The first students for the JD/LLMLE dual degree enroll in 2013.

2012

The Master of Judicial Studies Program enrolls its first class. Through the two-year degree, active judges study issues relating to judicial institutions, judicial behavior, and decision-making.

2014

Duke Law faculty approve a new dual degree, the JD/MA in Bioethics and Science Policy.

2017

The PreLaw Fellowship program welcomes its inaugural cohort. The goal of the program is to introduce undergraduate students, many from traditionally underrepresented communities, to the study of law and the benefits of a legal education.

2018

Kerry Abrams, a leading scholar of family law and immigration law and member of the University of Virginia law faculty, is appointed dean.

The Bolch Judicial Institute is established with a gift from Carl Bolch Jr. and Susan Bass Bolch to provide educational opportunities for judges, develop civic education initiatives, and conduct research and support teaching and scholarship.

Certificate in Public Interest and Public Service Law (PIPS) enrolls its first students. More than 200 students have since earned this credential by completing curricular and service requirements.

2020

Teaching and learning go online in March 2020 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Law School returns to in-person operations in the fall of 2021.

2022

A record number of new faculty join Duke Law in the 2022-23 academic year.

2024

The entering JD class is among the most selective in the school’s history and admissions trends demonstrate how much prospective students value a Duke Law education.

On Service

Stella Boswell T’90

Stella Boswell T’90 is associate dean of Public Interest and Pro Bono. She joined Duke Law in 2004 as a counselor in the Career and Professional Development Center.

Stella Boswell T’90 is associate dean of Public Interest and Pro Bono. She joined Duke Law in 2004 as a counselor in the Career and Professional Development Center.

In the 20 years I have worked at Duke Law, I have witnessed the significant expansion of resources for public interest careers and pro bono volunteerism, especially over the past decade. It has been rewarding to be part of this growth and inspiring to see the amazing things that our students accomplish — both during law school and in their continuing involvement after graduation.

Whether or not students plan to pursue a legal career in public service, they learn from their first semester as a 1L the value of even a small amount of volunteerism. Recent numbers tell the story: during the past academic year, Duke Law students provided more than 6,000 hours of pro bono service — 48% of those hours by 1Ls — in addition to nearly 50,000 hours of public service contributed through our 12 clinics.

Since it was established in 1991, Duke Law’s pro bono program has been an important way for students to develop their legal and professional skills, learn about gaps in legal services, and form the habit of providing pro bono service. Three years ago, as part of a program re-envisioning, we hired Daniel (D.J.) Dore, a former Legal Aid of North Carolina (LANC) attorney, to expand opportunities and outreach and train and supervise students. Under his leadership, the program has expanded to 15 student-led pro bono projects administered by the office, fully-funded spring and fall break pro bono trips, pop-up projects in partnership with local partners and other law schools, and independent projects.

For those aspiring to a public interest career, Duke Law offers the Certificate in Public Interest and Public Service Law. Since it was introduced in 2018, more than 200 students have pursued this additional credential by completing curricular and service requirements with mentoring and support from like-minded peers, faculty, counselors, administrators, and alumni.

Over time, we have expanded competitive funding available through alumni endowments supporting summer internships. In 2017, the Law School started offering guaranteed summer funding for unpaid or low-paid public interest internships for students who completed required service hours during the academic year. Duke Law also provides support for public interest students to attend conferences and travel for post-graduate interviews, and grants to assist with the costs of applying to and studying for a bar exam. And in 2022 we updated our long-standing Loan Repayment Assistance Program to allow graduates earning up to $90,000 to be eligible for partial coverage of their loan payments.

Indeed, alumni support has been crucial to expanding Duke Law’s public service initiatives and allowing graduates to begin their careers with considerable experience gained through summer internships, pro bono projects, clinics, and externships. We are especially proud to offer two endowed post-graduate fellowships that help launch graduates into work they are passionate about by allowing them to spend a year at an organization that could not otherwise afford to hire a new lawyer.

The Keller Fellowship, established by the Class of 1987 in 2018 to honor their classmate and longtime LANC attorney John Keller, provides salary and benefits for a graduate working at a public interest non-profit. And the Farrin Fellowship, funded in 2021 by James Farrin ’90 and Robin Farrin, supported two Class of 2023 graduates for a year of domestic non-profit legal work and will fund several more over the coming years.

The growth in the public interest space has been exciting. Our students and alumni inspire me every day with their passion and commitment to their work, and it is an honor to work with each of them.

“We have gone from being a small, regional law school with six faculty and a handful of students in 1924 to the highly influential and global law school we are today. That success and growth was the result of the committed members of the Duke Law community — students, faculty, staff, and alumni — who have always prioritized excellence in everything we’ve done.”

— Dean Kerry Abrams

Explore more at Duke Law Magazine

The Commons | Faculty Focus | Profiles | Alumni Notes | Sua Sponte